You’re probably a fan of David Shrigley and you don’t even know it. Acting in the fields of graphic art, studio art, books, music and animation, Shrigley has earned renown for making high-brow works on paper with a disturbing, punkish bite since the early 1990s. Though trained formally at the Glasgow School of Art, his drawings maintain an unskilled look, belied only by their being witty as hell. In late September, I met with Shrigley to talk about his career and the compilation What The Hell Are You Doing?: The Essential David Shrigley, which was published earlier this year and is now available in the US.

POP AND ART

RS: You could say that you were sort of lucky to have been born at a time where people are used to a sense of immediate gratification, intellectual, or aesthetic, or otherwise. It seems that that sensibility of our age seems to suit your work quite well.

DS: Yeah. But then again, I started making the work in an age prior to the Internet. I think if I'd started making the work ten years later, I might not have made any books. I might've just been an online thing, because the books were a means to an end to start with. They were a way to disseminate the work. I self-published my first several books and distributed them myself, or just gave them to people. The age of Internet obviously suits what I do in the sense that it wouldn't suit my work if I was making really subtle, abstract paintings.

RS: Had you been born ten years later or started making art ten years later, is there a chance that it would have inhibited you? Not all artists like the fact that their work can be distributed that quickly, that it can be that accessible. It takes away their sense of ownership. A lot of the time, it takes away their sense of authorship.

DS: Yeah, I suppose my work arrives unauthored, or without any reference to its author, but I don't mind that. I'm into the work being accessible. Its accessible nature, I think, is one of its strengths. So I don't think it's a weakness, or its something bad, that a lot of people could see your work, because that's essentially what it is. A lot of people could see it, and it gets sent all over the place, and obviously it'll just exist as an image on a computer for most people.

That's fine. When I was going up, in the 1970s, we had Thames and Hudson books of modern painting, and we looked at a reproduction of an Andy Warhol in black and white. I think the current situation is better, but it does lend itself to all sorts of ways and means of disseminating work, some of which are good, and some of which are bad. I embrace it, definitely.

RS: Given those kinds of facts about Pop, I don't suppose you've ever been approached by somebody wanting to do a t-shirt?

DS: I have many, many, many t-shirts. Some may even be for sale in this bookshop. I do a lot of t-shirts, and I do posters for stuff, often for bands. There's a friend of mine who's on bands in Glasgow, so I do a lot of posters for that, but I don't really sell posters of my work.

RS: How about tattoos?

DS: Those are on my website. You will see the horrible reality of my tattoo design, the tattoo design branch of my oeuvre, which is really weird. I don't like tattoos, but somehow, I just ended up being a de facto tattoo designer, totally by accident.

Somebody asked me if they could use one of my images as a tattoo, and I was like, “If you really want to.” And then I put the image on the website, and it just sort of started to snowball from there. People started to have loads of images of mine on tattoo. And then I started to design them, and then I did events where I would draw tattoos, and I thought, “Oh, what am I doing? This is ridiculous.”

RS: Do you have any tattoos yourself?

DS: No. I'm not really a tattoo kind of guy. I don't think I look like the kind of person who would have a tattoo in any kind of frat house way.

GOTH, GLASGOW, AND GALLERIES

RS: A lot of my favorite drawings of yours have something to do with death, graveyards, etc. There's got to be something virile and attractive and sexy about being really into death, maybe even doing things that might be perceived as goth, like Ian Curtis. Did you ever draw with the idea that people are going to be impressed by how dark you were?

DS: No. Well, it's supposed to be funny not furious. Although Ian Curtis and I were born in the same town, in Macclesfield, outside Manchester.

RS: Fun fact!

DS: Yeah. Famous people from Macclesfield: Ian Curtis and, perhaps, me.

I kind of do have a soft spot for goth, I have to say as an aside. I guess this is supposed to be funny, but I used to be a bit of a goth. I was really into Bauhaus in the early 80s, and I still kind of have a thing for dark metal and stuff like that. I got asked by this band called the Skull Defekts to do a cover for them. They’re a Swedish kind of no-wave band, but very goth, and kind of wonderful. Kind of great in their gothness. But yeah, there's quite a lot about death in my work.

RS: What are you listening to right now?

DS: Well, I would recommend the current Skull Defekts release, which has a guy called Daniel Higgs, who's an American. He's their new vocalist, and it's called “Peer Amid.” That's really good. I like guitar-based stuff and rock music. I guess Dinosaur Junior and The Fall are probably my two favorite bands.

RS: Were I to narrow it down to Scotland or to Glasgow…

DS: That I haven't collaborated with? Orange Juice is one of my favorite bands, and Teenage Fan Club I always loved, though I guess I don't really play their records anymore. I still love those first few records. Jesus and Mary Chain, first record. That was a great record. I like a lot of things, but then I have to start mentioning people who I actually know. Malcolm Middleton I really like, but Malcolm's become a friend of mine. I think he's a great singer-songwriter. Very underrated.

RS: Those are all from Glasgow, just to be clear?

DS: Yeah. I think technically Jesus and Mary Chain are from East Kilbride, [the lowlands of Scotland].

RS: Nobody who reads this interview is going to know where that is.

DS: Some might. But yeah, there's a lot of great music in Glasgow. I think that's one of the things that keeps me in Glasgow.

RS: Do you still see live shows?

DS: Oh yeah. A few years ago I stopped going to art events and decided that would only go to music events, So I never go to openings or art shows. I mean, I go and see exhibitions, but I never go to the social events. I just go to music events. That's my entire social life: going to dinner with my wife and going to see bands. I go to see bands every week. We don't have any kids, so I guess I'm allowed out.

RS: From your drawings, I could see why you might not be that crazy about openings in particular.

DS: When I was not long out of art school, I suppose perceived the art world and all the people in the art world, as not having a lot of integrity, shall we say.

RS: Do you have warmer feelings about art, the gallery system or commercial art now?

DS: Well yeah. I can't bite the hands that feeds me. My mortgage is paid by the world of fine art, so I'm obviously more pragmatic about my critique of it now. But yeah, I think there's always going to be people who are making stuff that isn't interesting, and are slightly mercenary about it.

THE MUSIC WORLD

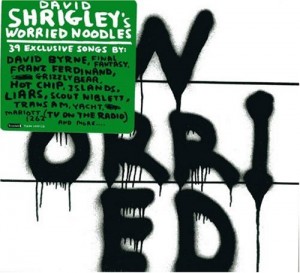

Reid Singer: Could tell me a bit about how the record Worried Noodles was conceived?

David Shrigley: Well, the record label that put it out was called Tomlab out in Cologne. They asked if I'd like to make a record cover for one of their bands. At the time when they asked me, I didn't really like any of the bands on their label, so I avoided the issue.

Eventually, they suggested we just do a record cover without a record in it, and it would just be an art work. A conceptual art work. I thought that sounded great so we did it. We made it with this gate fold sleeve with a dust sleeve inside it that had an apology for their not being a record in it.

I thought it wasn't quite enough, so I wrote this song book where I wrote lyrics as if they were written on the sleeve of a vinyl LP, as if they were written by the musician, perhaps. They were a bit like concrete poetry meets a version of lyrics, but obviously I never had any intention of them being recorded. I never had any music in my head when I wrote them, so they were just that, really. Concrete poetry, technically speaking.

Inevitably, the record label told me we had to got to get some bands to record this. I really wondered whether anybody would want to.

I didn't really have to do with inviting the people, apart from a few big names that we either people that I knew or I sort of had some link to. Because I sort of had a contact with David Byrne, I asked him if he would do it. And I knew Franz Ferdinand a little bit, who's a Glasgow band. And a few others. Then the rest was curated by the record label. That was kind of great, actually. It was probably a lot better that way, because if I'd curated it, by bands that I really like, it would've ended up being a rock record rather than a pop record.

RS: Did you become fans of any of the bands that were on the album?

DS: Oh yeah. Definitely. There were several. Several of the acts there who I really got to know through the recording, like Scout Niblett, I hadn't really heard before, then I sort of became acquainted with her a little bit. I met her a few times and have been to see her a few times, and I really like her stuff. One or two others: R. Stevie Moore, I got to know through that experience, and I've become friends with R. Stevie Moore, and helped put on shows for him and things. And one or two others as well. It was a really great experience, but an odd one that you couldn't really replicate.

RS: So you don't expect to do it again.

DS: No. I guess I make work in a huge variety of media, almost absurdly large media. I'm making an opera at the moment with a classical composer. I guess that's as far as I've gotten from the world of fine art, but that's another kind of project I was asked to do. I just wanted to write a play, I suppose, and I really liked this composer's work. I think it'll be basically a collaboration between me, the composer and the producer. I've essentially written the libretto, as it were, like a play. But I think it'll be kind of cool, because he's a really great composer.

RS: What's the composer's name?

DS: We haven't really started publicizing it yet. The guy's called David Fennessy, an Irish guy who lives in Glasgow. I knew his work before. I've seen a couple of things that he'd done. It's really interesting, kind of angular, modern composition. That's going up in Glasgow in November.

In terms of what I do, and the variety of it, I don't know. I'm not really a dilettante. I'll never do another opera, for example, but I want to do this one, and I think I'm serious about it. I think it can be good, because I'm surrounding myself with some really talented people. It'll probably be good in spite of my contribution rather than because of it.

I guess I work in a lot of different media, and I'm not afraid to do different stuff, and I like to do things, different projects. I'm not really bound by craft. My craft is some form of notation, rather than drawing. I'm kind of unafraid to make mistakes, but I don't just do something just because I fancy it. I'm serious about it. I will have spent a lot of time doing my opera, for example. As long as it's not shite, what I'm doing, then it's alright.

Comments on this entry are closed.