If a curator’s job is to conserve and care for what exactly are we doing with all those tumblrs? I’m not entirely sure, but since Rhizome’s Digital Conservator Ben Fino-Radin seems to do what the classic definition of curator does I figured I’d talk to him about it. It’s good preparation for the panel I’ll be on this weekend at the Woodstock Digital Festival titled, Making Art vs. Curating Art: The Peculiar Case of New Media but also this year’s Art & Reality Conference in Moscow, where I’ll be leading the online curating section of the conference. Needless to say, this will be the first of many interviews this summer, in which I talk to New Media art experts and layman alike about what curation means to them.

Paddy Johnson: So one of the things I wanted to talk to you about is the difference between curation, digital curation and new media curation, and digital conservation. Curation, as I understand it, means to “care for” something. Given that that’s the case, I wondered if you could talk about your role as someone who, by definition, is doing that.

Ben Fino-Radin: Right, well I think it’s interesting that you brought up sort of the traditional definition of what a curator is, because obviously, that’s something that culturally, at least in popular culture, is totally lost. But the definition you’re referencing is still used in rare books and manuscript libraries. Essentially, what I do is similar to what a curator of manuscripts does. But, of course, with a lot of other technical stuff looped in there.

PJ: Right. But you call yourself something different, right?

BF: Well yeah, the purpose of a job title is to communicate it is that you do, and I don’t think that the term curator communicates what I’m doing. I think conservator does communicate it much more effectively, because when you think of conservation, there’s no mistake there. Nobody thinks like, “Oh, he’s just picking his favorite art” or something like that. Because that’s not what I do at all.

PJ: (laughs) Right.

BF: …So the second step of what I do is conservation, ensuring long-term permanent access to works of art. But the first stage of that is curation, because it’s essentially seeking out what is most at risk, what is most significant, and what’s been forgotten. What hasn’t been written into history yet, but should be.

PJ: Just from a nuts and bolts perspective on things, I don’t really have an idea of how you would spend your time at Rhizome.

BF: (laughs)

PJ: Like, are you making sure that it’s easier to find things on Artbase, or is that something that [Rhizome Director of Technology] Nick Hasty would take care of because it’s a programming thing?

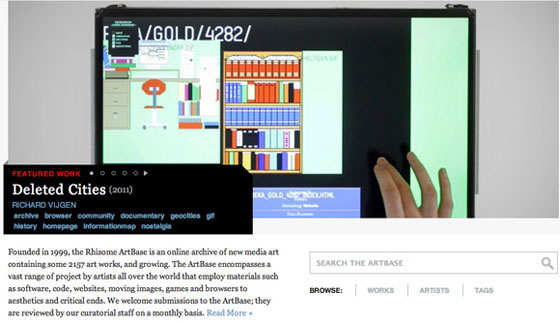

BF: Well in terms of searchability and browsability, that’s really a collaborative effort. But in terms of how I spend my time at Rhizome, I can’t really say “here’s what I do on any given day” One project that’s on my plate right now, as I’m sure you saw, is a new sort of interface for the front end of the catalog. So that was specifically with the purpose of providing greater entry points: better browsability and findability of the work. But a lot of what I’m doing is going through our backlogs. So we have just over 2100 works in the collection, and only 500 of those are actually hosted on our servers, so a lot of what I’m doing right now is actually gathering materials: going through and using different tools to basically scrape the web, and back these things up on our servers, and host them.

If it’s on our server, A: we can prevent ‘Link Rot’ and B: we can analyze the actual digital materials and derive technical metadata from that that helps us maintain access. For instance, if we’re moving the collection to a different server, we have metadata about certain works where we know what frameworks we need them to operate within, or from an end-user perspective, there are certain client-side things like proprietary plug-ins, like we have a lot of Shockwave, and that’s something that doesn’t really work anymore. You can actually install Shockwave, and it’ll work, but it’s kind of backwards.

It’s still useful to have that metadata, because eventually, if we have some sort of physical footprint for the collection, which I think moving forward is really important because as I wrote in the piece for the Creators Project, there are these sort of subtle artifactual qualities to the stuff where emulation is necessary, and currently, you can’t deliver client-side emulation, really.

So having a physical footprint is actually kind of important for this stuff. So in that case, the technical metadata is really important. For instance, we can pull up every work that needs to be displayed on Netscape 3.0, and for our Netscape 3.0 object in the database, we have this semantic relationship between that and what environments are required to operate. So, a lot of what I’m doing right now is the web archiving stuff. We’re basically planning to move to a new backend for the whole collection. So currently, a record is sort of flat, like when you look at something, you get related artworks, but it’s still sort of based on keywords which is sort of… weak.

PJ: I’m sorry, what is metadata?

BF: (laughs) Metadata by classic definition is “data about data’, but (laughs) that doesn’t really mean anything. Metadata is structured, controlled information about an information resource. So basically, wall-text is metadata, when you look at a work in Artbase, its catalog entry is metadata. When you are looking at Netflix, that’s all metadata, the Title, the Director, things like that.

What I’m doing is allowing us to have records for artworks, people, events, places, institutions… So that each of those entities has an authority record, in other words, there is an object in the database where—let’s say Eyebeam. So that when you say that—”this exhibition was at Eyebeam and so was this exhibition”—those are correlated in a really tight way where you know you could potentially say that Eyebeam is therefore related to this artist, it’s therefore related to this work and this exhibition, and things like that. So, basically a lot of what I’m doing right now is collecting materials and also building out our infrastructure for not just cataloging the works but also the technical metadata.

PJ: So an authority record can be a person’s name, or could also be an organization? It’s way to identify something?

BF: Yeah, exactly. When you are entering metadata, you are pointing to this object. Otherwise, you’re just typing in text—which is useless, it makes it so your database isn’t… like, your Facebook profile, that’s your authority record because there’s only one view.

PJ: Right…and it sort of seems to be based on some of the things you’re saying that preserving the narrative as it was once told is important in digital conservation. But people’s intentions change, and so I wonder if a lot of your role is talking to the artist to find out what they want preserved, or if at a certain point do you just say ‘well this is important, so I want to preserve it.’

BF: I mean, yeah, there is always a lot of conversation involved. In terms of what’s worth preserving, there’s never really been any sort of difference of opinion there at all. I mean, I’ve never encountered a situation where I’ve emailed an artist, and said “Hey this link is dead”, because if it’s dead it usually means can’t get in touch with them anyway. These are things that all archivists do, and all conservators do. And it’s basically knowledge gathering, and it’s extra important with internet art because the narrative and the meaning of the work is really embedded in the digital materials and the social context surrounding it.

PJ: That actually kind of leads me to one of the core questions I had, which is: to what extent can we preserve and communicate this? I mean, all of this browser-based art has been very reliant upon social context, and also the browser itself.

BF: Yeah, totally. So to go back to the Creators Project thing, the reason I showed just really basic pieces was because it was a big deal to be able to do hypertext, like interactive hypertext with gritty, pixely, non-anti-aliased fonts. So, that’s just an example of that—something that was at one time special, but is not documented properly or explained, and now is just sort of lost.

So, the way I think about it is that there are some works that we will be able to preserve, and their full meaning will just be inherent, no matter what, just because that’s the nature of the work. Other works will require more context and framing, and that’s something that has a tradition, in the museum, and in archives. I sort of think of the Artbase at its ideal state as an archival box that has these documents that maybe some day will be stripped of their larger meaning… Like if you think about somebody’s personal papers, that archival box, there’s no way that can ever totally, fully communicate the entire meaning of that person’s life as it actually was. They’re all just artifacts that require interpretation.

PJ: Right, right. So, is there anything that needs to be saved that we don’t know how to save?

BF: Just generally, anything that uses an API that we have no control over. It’s very unlikely that we’ll be able to establish some relationship with Google where they’re going to provide us with an archived data set that we can draw upon. Documentation is really just as important, because it’s not our sole mission to preserve the user experience, but if we can’t solve that, then it obviously doesn’t stop there, it obviously moves onto documentation and that’s been a very important strategy in the preservation of video games. People in that community doing preservation work rely heavily on screen captures of playthroughs, and it’s actually very effective because it provides a lot, and it preserves a user’s perspective or a viewer’s perspective. And in the archive, taking a user-centered perspective, having the ability to just watch video documentation of a work in action is actually, from a research perspective, more useful than having the actual work in some cases. If what you’re using it for is just simply research, it’s kind of a really elegant solution. So, the short answer is future proof documentation methods.

PJ: How many contemporaries do you have? Like, how many people have a job like you do?

BF: Well, there’s a lot of people in disparate fields, there’s a lot of people in humanities, there’s a lot of people in archives, the Maryland Institute for Technology and the Humanities is doing great work, NYPL labs, Jason Scott Archive Team, The Internet Archive…I mean we’re members of the National Digital Stewardship Alliance, and they have just over 200 members. They’re all part of organizations doing at least vaguely related work, a lot of them are academic libraries that are just doing digital preservation for library stuff, so that’s a very different ballgame because with digital preservation in the library world, your goal is not to preserve an artifact, your goal is to preserve information so the carrier is readable. It doesn’t matter if something is in its original font, it doesn’t matter if something is in its original format, it’s just all about the content. But broadly speaking there’s a lot of people doing this work, but not many within museums and the preservation of digital artifacts.

PJ: So you’re not alone, but…(laughs)

BF: I mean, it’s really an emerging field.

Comments on this entry are closed.