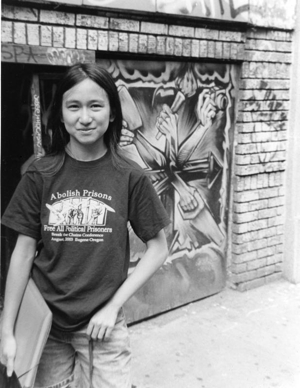

In the third of four ABC No Rio interviews, I spoke to activist, writer, and photographer Victoria Law. A Queens native, she first came to ABC No Rio for a punk show at the age of fifteen. It wasn’t until a few years later, when she became interested in activism, that she came back after reading about the “Food Not Bombs” program and steadily increased her involvement. By nineteen, she co-founded the New York chapter of the “Books Through Bars” Program at No Rio, later serving as treasurer and organizing arts programs which addressed prisons as a system of racial and gender control. She went on to independently create forums for incarcerated women and social justice activism, through the zine compilation of stories from female prisoners Tenacious: a Zine of Art and Writings from Women in Prison, and her books Resistance Behind Bars: The Struggles of Incarcerated Women, and Don’t Leave Your Friends Behind: Concrete Ways to Support Families in Social Justice Movements and Communities.

Whitney Kimball: What was it like when you started getting involved with the space [in 1995]? What made you want to get involved?

Victoria Law: I originally got involved with ABC No Rio by coming to the Sunday Food Not Bombs sharing. It was basically a group that got food and shared it with people, and it didn’t necessarily have to be homeless people or people in need, it could just be [people passing by]. And a lot of people who were living upstairs were involved with Food Not Bombs at the time, so I ended up getting to know them, and they kind of took me under their wing as the new girl in the scene.

So, I think in the summer of 1996, some of the people upstairs decided to do an art camp for a week for the neighborhood kids. I only helped out the first day and the last day of this one-week art camp. The first day it was like a dozen to twenty kids from the neighborhood who took all the different colors of paint and mixed them together and made various shades of brown [laughs]…because that’s what happens when you mix all your paints together. And then the last day I was there, there was a whittling down of the numbers because kids had gotten in trouble, got grounded, one kid threw a rock through the window of a doorman building and got caught, so his dad had to pay for this gigantic window, and so his dad grounded him for life…

…so it was really like less than half a dozen kids by the end of the week because they had all just kind of fallen off. There was a kids’ parade, because over the course of the week, they’d made weird artsy things, costumes, they had a kids’ parade through the neighborhood. So again, it was one of those things where somebody had just said “Hey, we’re doing this, you might wanna come and help out.” This idea of just being like “Welcome. This is what we do, and if you wanna come, you’re invited.”

WK: So what was the organization like back then? If you wanted to start a project, what was the process like in getting something going?

VL: Well, at the time, it was just the ground floor and the basement. People were living upstairs, but there wasn’t space to actually do projects upstairs until late 1997. When people moved out there, there was space to…you know…but if you said, I wanna do this art show or project, the space was totally open to do that. In February or March of 1997, another woman and I proposed doing an art show of art by and about the Fifth Street Squatters, which was a neighborhood squat that had been evicted recently. It was sort of a celebration of that building and the people in that building– and it was fine. It wasn’t like you had to go through some long process, it was “oh, we want to do this,” and people were like “Great. Here’s what’s open.”

[Several witnesses attest that the city began demolishing the Fifth Street Squat with people still inside. A 1997 report by Steven Wishnia begins:

At 4:30 PM on Monday, February 10, a city-hired wrecking crane punched a hole in the fifth floor of the squat at 537-539 East Fifth Street. The scooper swung back and slammed into the sixth floor, battering open another hole more than ten feet wide. The building wasn’t empty. Squatter Brad Will was still inside, where he’d been hiding ever since the city demolition crew arrived on the block at 9:00 that morning. They had already tried to knock the building down earlier that afternoon with him in-side, chomping off half of the parapet before Will emerged onto the roof. When police couldn’t find him, they started again. “It was fuckin’ scary, man,” said Will, a 26-year-old bicycle messenger who had been living at 537 for two years. “I could feel the walls shake. I clung to the walls and started crying because it was a strong building and it was a shame to tear it down. I loved that building.”

We found this film clip on YouTube of the demolition.]

WK: Was the squatting movement winding down at that point?

VL: I think I’d caught the tail end of it. Some people tell you about the early nineties, late eighties, and I think by the time I came on, it was kind of…not winding down, but settling down more. It seemed like there were more squats being evicted than being squatted.

WK: Did you know any of the people involved in that and how they’d managed to remain in their buildings for so long?

VL: Through ABC No Rio, I got to know some people, just because there was a big crossover between the squatting scene and people involved with ABC No Rio. In part because there was squatting upstairs at ABC No Rio, and in part because the Punk Show and the punk squatters had a big crossover as well. So I got to know some people, and they would sometimes tell stories about how they stayed in their building, or stories about how they managed to outwit the cops or the utilities companies, or whatever.

But then they would also talk about all the buildings that got lost. Apparently on Eighth Street, between Avenue B and Avenue C—there are no squatted buildings there now, as far as I know, but in the late eighties, early nineties, that was totally a squatted area with squats on both sides of the streets. Different levels of political squatters, some people were just like “Oh, I need a free place to live, who cares…” and other people who were like “Housing is a right, this is a political statement.” But people would talk about how it was kind of like living in this weird little squatted enclave. You could sit on your fire escape and yell to the person on the next fire escape who was also a squatter. And none of that’s there now. That all was gone by the time I came around.

WK: Would you mind just talking a little bit about the [New York] Books Through Bars program and how you got that off the ground? It seems now that there are more groups outside of New York…

VL: Well, I don’t want to make it seem like Books Through Bars New York was the catalyst for that. One of the people who advised us on Books Through Bars was this group in Philadelphia, which had been around for much longer. He suggested that we use the name Books Through Bars.

So originally it was seen as a way to send people books inside prisons, but particularly books that wouldn’t normally be found in prisons. If prisons have a library, often times it will be whatever’s donated. So for a women’s prison it’ll be crappy romance novels, other mass market drugstore fiction, maybe some textbooks that are out of date, maybe not. But nothing that really pokes people a little bit more, encourages people to think a little bit more critically. It could just be a novel that encourages you to think a little bit more critically, forces you to look at what’s going on, instead of just being like “Let me escape from my prison cell temporarily.” So hm—why is it that everybody around here is black, brown, and poor? Why is it that every woman here has a history of domestic violence? What’s going on here?

So it just challenges people a little bit more, and the [idea] was to send more radical books, like the Black Panthers or Malcolm X or Assata Shakur. Things that a library was never on its own going to order.

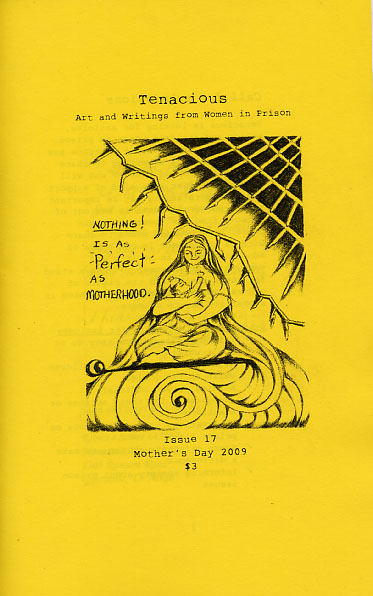

Issue 17 of "Tenacious: a Zine of Art and Writings By Women in Prison." (Photo courtesy of microcosm publishing)

WK: Would the prison ever frown on the submissions, or do they accept everything?

VL: One of the things about partnering with Blackout Books was that, because most prisons allow books to go to individuals in prison through a bookstore—so, say, sending it to the Attica Prison Library and having the Attica Prison Library being like, oh no, you do not get to send any of these books and tossing them in the garbage—people in the Attica Prison would be able to get those books.

WK: So they wouldn’t check them?

VL: Well, different prisons have different regulations. Not in terms of content, but mostly in terms of the condition of the book. Some can say “no used books,” because ostensibly with used books, you might be able to hide drugs or weapons. But we think it’s really a way for them to screen out buying a used book on Amazon, or taking a book off their shelf and being able to send it to a loved one in prison. Some might say no hardcovers, because maybe you could hit somebody in the head with it. There are all these rules that tie back in some way to the safety and security of the institution, but, really, that [dining] plate could also be used for that. It’s been less so with the actual content, in terms of what can and can’t get in.

WK: On the site, there’s a link to some artwork that a person had sent back from the program. What’s the feedback you get from the program? Do you receive letters or correspond with anyone who got the books after the fact?

VL: Some people, yes. Some would send back thank you letters, some individual volunteers started correspondences with individuals they’d sent books to. I think there’s really something about letters that touch somebody so much. The way the Books Through Bars program works is that individual people in prison sent a letter, like “I would like a book on xyz,” “I would like this, that, or the other book,” or “I’m locked in here for x number of hours a day, please just send me a book.” Some people write long letters, some people write short letters. Some people write letters that are just misspelled and then you’ll see a “PS, by the way, I’m his cellmate, I have to write this because he can’t write it all.” And you’re like, woah.

So depending on what the letter is, different people might say, “Oh, I’ll send you a book, and I’ll write you a letter.” Or “I’ll just send you a book.” It depends on the person volunteering. I’ve gotten to know several women in prison that way, when I thought, “Oh, that’s really interesting, you’re not asking for some fiction to escape, but you’re asking for something more in-depth– maybe I’ll drop you a line as well as send you a book.”

WK: You’ve written several books now on situations in prison. Was the Books Through Bars program was a catalyst for this?

VL: It definitely was one of the catalysts, because I kind of see this as a trajectory about learning about prisons and framing my ideas about prisons. Who goes to prisons and why, the importance of education and learning. But also seeing what different people ask for, and for me it’s about making connections with some of those people who ask for things that I find more interesting. I’m like, oh, you actually want books on anarchism. Why would a woman in prison want that? And also how does that then interact with the way they perceive prisons, if they’re asking for radical history or politics? Talking about prison dynamics and prison socialization, how do prisons repeat the violence that you see outside, et cetera, et cetera. So it’s sort of interesting to see how that all plays out. So yes, it was a catalyst, but it also continues to be a major part of how my perceptions of prisons are informed.

WK: Did ABC No Rio help you to start realizing that you could put together these programs?

VL: Yeah. I think one of the wonderful things about No Rio is that when I first started volunteering, I was in high school. I didn’t know anything about putting together an art show or putting together anything. I was like most high school students, especially high schools that don’t have a lot of resources. So they’re not preparing people for do-it-yourself, or you-can-do-it— it’s more like, yeah, no. [Laughs] Just sit there and be warehoused, and eventually, you’ll go someplace else and be warehoused. But it wasn’t like nobody told me, “No, Vikki, you can’t do an art show.”

At that time, there may not have been a lot of guidance in how to put together an art show, nobody told me about writing press releases or getting publicity. So it’s like we just did an art show and we’d put fliers everywhere. This was back when you could actually tape fliers to lampposts and not get arrested for doing so. And be like, great, we have an art show, and there would be an opening, and all your friends would come, and everybody from the different squats would come. And some other old-time No Rio [people would come]. And there would be gallery hours, so learning as you go, but it wasn’t like anybody was like, “no, you can’t do it,” or “no, you’re not doing it wrong.” It’s like “Okay, great, you’re gonna put together an art show, here’s where the drills are, here’s where the screws are, go for it.

WK: Were there any other high school students when you started volunteering there?

VL: There were a couple. I don’t think they stayed around because they went to school out of state. There were some people who were either in college or just finishing college who were around, and I think those were the first people who took me under their wing, just because I was a couple of years younger.

WK: Were they all activists?

VL: Yeah.

WK: What was their background like? It was people who were interested in activism professionally?

VL: Yes. Some of them in the mid-nineties, there was also a lot of crossover between people who were interested in radical politics, changing the world, but also while doing really concrete type of actions, people who were squatting and people who were at No Rio. So it was this crossover type of thing…

A lot of people were working around the case of Mumia Abu-Jamal, because he was scheduled to be executed in August of 1995. So there were constant meetings about that, people were talking about doing guerilla performance art on the steps or the lobby of NBC or ABC— there was one news channel which refused to cover Mumia, they were like, “Oh, we’ll just do it once he’s been executed, because then it’ll be a news story.” So people actually talked about doing guerilla performance, clogging the lobby, holding banners, doing a performance about why this shouldn’t be what the case was, why it shouldn’t be swept under the rug. People were combining that creativity and art with the message they wanted to get out.

So instead of saying, we’ll do a rally, and no one will stop to look at us because it’s a rally, and no one will be interested. But people might stop to be like “Who are these people in these weird costumes? Oh, and by the way, we can’t get into our building, so I guess we’ll stay here and watch this.” As opposed to “We can’t get into our building, so we’ll go get coffee.”

WK: Do you see many alternative spaces that foster that kind of environment for young activists now, or do you think it’s changed?

VL: I don’t want to say I don’t see any, because as an older activist, I’m not plugged into what younger activists might be going in and out of. […] One thing that was pointed out to me was that these days, places where people hang out and congregate tend to be places where you have to consume something, like the bar. You have to consume alcohol, you go to the coffee shop, you have to consume, and there’s not really places where you can just kind of go and hang out. So they pointed out that No Rio is one of the places where you’re not expected to go and somehow pay for it.

WK: As you continued working there, did you see the space or the organization change?

VL: I think the space has changed dramatically. In 1997, the people who were living there moved out, as part of the deal with HPD. Since they couldn’t put us in a program that would allow us to have the ground floor and the basement as a community space and continue to have people living there—it didn’t fit into one of their program boxes—they said we could have a full-fledged community center, or we can continue trying to evict you. And so the people who were living upstairs were like, well, we would rather have a community center than have it become a yuppie condo with a Blockbuster on the first floor.

And some of the people who lived there really had adamant ideas as to what kind of community space they wanted, one of them knew there was a zine library up in a squat in the South Bronx. Back in 1995, people would come to Blackout Books and say “Oh, I’d heard that you had a zine library, too,” and I would be like, “Yeah, it’s up in the South Bronx.” Nope. Not going up there. You’d give them directions, but they were no longer interested. So he really wanted to move it down to ABC No Rio, and people could just have to walk a few blocks over, it would be more accessible, it wouldn’t have to be like trekking all the way to the South Bronx and invading somebody else’s neighborhood to look at zines.

WK: Is that when you started the darkroom?

VL: Yeah, so that was also when we started the darkroom. There had been a couple of squat evictions earlier that year, most notably the Fifth Street squat; basically, there was a fire, and the fire department then evacuated the building and wouldn’t even let people go back in and get their stuff. Even though there was a court order that said the city had to go let people retrieve their belongings before demolishing the building, the city didn’t, and they demolished the building anyway. There were several court orders, and people actually took pictures, but this was way before digital photography. I don’t know if it existed, but it wasn’t very common, so we had negatives and no darkroom access. So originally, we were like, “If we have a darkroom, in case anything happens like this where somebody needs to develop their film, print pictures and have it for court by 9 AM and it’s 10 PM the night before, we’ve got it.” Because we would call around and try to figure out darkroom access, and we just weren’t able to. So the darkroom kind of came out of that, at the time, an urgent need to have these facilities that are open to the community. Where it’s not necessarily where you have to be a professional photographer, or pay money to be a part of somebody else’s darkroom, or affiliated with some sort of institution– you should just be able to go and use it.

WK: Was there any meeting or event there that you felt really made a change in the community or pulled people in who you wouldn’t have expected? Or just any memory from the space that sticks in your mind?

VL: There are a couple of memories of the space…fast-forwarding a few years, there was the haunted house for kids that we did, maybe 2004. We dressed up the gallery, the basement, and the second floor as a haunted house, and basically it’s spooky things, someone telling a story about something that involves a head on a platter, you know, because there’s a platter and you pull it off, and there’s a head there. Freak all the kids out, the kids would literally come barrelling down the stairs and out the door. So we got a trickle of kids here and there.

And then one guy came and liked it so much that he went up and down the street telling every single person on the street—every single kid trick-or-treating, every single person, every single teenager—”you have to go to this, it’s a free haunted house, and it’s amazing!” And suddenly, we just got mobbed. We literally had four hundred kids who came within two hours, and we were all exhausted by the end of it. Not even the end of the night, it was like eight o’clock, and we were like, “We’re done! We’re done. There’s just no way we can do anything more.” [Laughs]

So for me, it was just like oh my God—that power of being able to just do something. All the kids loved it, all the parents loved it, parents were coming out with their kids. The little kids would be crying, they really did not like this, their moms carrying them out and pulling out their phones to call their friends to say “You really have to come to this haunted house, bring your kids, mine is crying right now.”

WK: Have you worked for any other nonprofits or activist groups? How was that different?

VL: I think a lot of other nonprofit activist or arts groups don’t have that same “take-the-ball-and-run-with-it.” It’s more of a top-down thing where you have to run things by the director, the director has to approve. I worked at one place where I wanted to do more political art stuff, or art with more politics than just like “This is pretty pictures.” I got shot down by the director, who was afraid that the board of directors would be really unhappy if we had more political art shows, they were more worried about the image of the group, and it was like, well, I’m not really interested in art-for-art’s-sake. Because I don’t have a traditional fine arts background, and for me, one of the things I really like about art is that it can bridge [gaps between people].

So I feel like, with No Rio, there’s a kind of exceptional way of take-the-ball-and-run-with-it.

WK: How old were you when you set up the darkroom there?

VL: It was ’97, so I must have been twenty. It was me and a bunch of high school kids who were doing Food Not Bombs, so I was sort of the old lady in this group. None of us had any construction skills, it was the saddest thing ever. We would plaster over all this stuff, sand it, sand it too much, have to plaster again [Laughs]. We would have these ridiculous workdays where none of us knew what we were doing, but we were like, yes, we want to build the darkroom. Luckily, some people who actually had those skills came in to do the electricity and the plumbing. They came in and looked and they were like “well, I guess that’s an okay plastering job…” [Laughs]

WK: But it’s held on for a really long time, right?

VL: Yeah. But I think it is perhaps not because we had the exceptional skills at the ages of sixteen to twenty. It’s more that some of the stuff that’s held on has been stuff that other people have done—it wasn’t necessarily a meant-to-last thing, because we were like we’ll have this new building, then we’ll have a real darkroom, but in the meantime, we want a darkroom now. I think any other group would have said there have to be adults involved, you can’t have sixteen-year-olds learning how to do this kind of stuff, taking charge of their lives; sixteen-year-olds are supposed to be interns who go out for coffee. Or file, or sweep—not necessarily people who are going to be like “I am going to take this on, even if I don’t really know how to do it.”

WK: Do you think that that spirit will continue in the new building?

VL: I think it will. I think that will manifest itself differently in a new building, because hopefully in a new building, there will be no need to, say, fix pieces of wall that are missing or deal with plumbing problems or lack-of-plumbing problems. But I think that it’s also exciting where it gives you that finished space, what kind of programs can you imagine doing in that space? Not just “well, here are the limitations. Our place isn’t that sound-proof, so your noise has to end at a certain time, or we can’t schedule things too closely together.”

WK: What was it like being the treasurer for a while, and how was that handed to you?

VL: The punk matinee was the board of directors, and I don’t remember why they were all stepping down, but they were. I think I had actually volunteered to be secretary, because in high school, math was not my strong suit [laughs]. And for some reason, I ended up treasurer, and I don’t know why that was, why I got the job that I didn’t actually want. So it was actually good for me to do this, because I learned that being treasurer and doing budgets and numbers is not the same as the abstract math that you learned in school.

From that, I learned how to do budgets and grants, which is something that, again, I think a more typical nonprofit activist space would not give to the totally new twenty-year-old with no experience and a really shaky understanding of math. Do a grant. So I learned how to write grants. I learned how to try to talk to grant people, and there were a couple of times where it wasn’t great because I wasn’t prepared. I think once or twice, Steven [Englander] and I met with people, and I couldn’t answer questions, and they were like, you need to learn how to do that. But again, it was a learning experience that I wouldn’t think I would have gotten, had I been a low person on the totem pole in another group. It was like “Here, you can do this.”

One of the things I did was got a grant for a prisoner art show that I helped coordinate in 1998. We were getting art from people in prison, and some of it was amazing— things made out of toothpicks. Why can you get toothpicks, but you can’t get hardcover books? But we’d get things like ships made of toothpicks. Some of it was going to postage, some of it to artist honorariums. But there were so many artists that the honorariums— we could just give them, like, two bucks.

So I applied to the North Star Fund for being able to do additional publicity for the show, because I thought, this is huge, and this was before prison art became a thing, before people were talking about prison justice issues a lot. We needed money to be able to hang the stuff, the postage costs of paying for shipping, because we weren’t going to ask people in prison who make, like, two cents an hour to pay for shipping. We also wanted to pay them a better honorarium, because if we could pay them a better honorarium, because if we could pay them fifteen bucks instead of seven bucks, that’s gonna go a long way. And we got the grant.

It was really amazing to have the skill set now to be able to write this grant, lay out the budget, go to a meeting, and explain exactly why we wanted this. Granted, the North Star Fund is kind of sympathetic to things like prison art shows, activist art, stuff like that. It’s not like I went to the Rockefeller Foundation. [Laughs]

But just being able to do that, and now everyone gets a better honorarium. It means instead of being like “Do I want to call my mom, or do I want to buy soap?” Now it’s like “Oh, look, I can do both!” So that was a really powerful skill set that I’d accumulated along the way. It wasn’t like I loved doing grants, but now I could get the show and have it be better, more meaningful to everybody all around.

WK: How long was the show up?

VL: It was up for a month, a month and a half. It actually got a review in the New York Times.

The show then traveled to other places because another woman, who was newly active at No Rio, said “Hey, I’ve got a friend who runs a gallery or is involved in an art space…” something that had to do with the arts in Texas. “Let me call him and see if he’ll have you do the show there.”

And so the show went to Texas. It was kind of that jumping-off point where we realized it could go other places, it didn’t necessarily have to be this one-off show.

WK: Do you think the building will attract a different crowd than it does now?

VL: I think it will attract a larger variety of people. I feel like a lot of people come by No Rio, and they find it really daunting. There’s this hallway, they’re like “What is this…” I think the conditions of the building make it really hard for people to be comfortable. You kind of have to be used to this disintegrating squalor.

One of the things we’re excited about is to envision, what does this mean for it to be accessible to everybody? Not just people who have all these abilities that we assume that people have. In the new building, this can really be a space for everyone; you can roll your stroller in, you can roll your wheelchair…you don’t necessarily have to be able to navigate stairs by yourself, you don’t necessarily have to be able to get in small doorways.

WK: Are you excited for the renovation? Any feelings either way?

VL: I’m excited for the finished product. I’ll probably be really sad about losing the history of the building; right now I can go through the building and point out different places from different eras. We put up a couple pictures in the darkroom of what it used to look like, with a couple different pictures of workdays and what it looked like in the printing room with the big sink…I put up a big picture of what the wall looked like when it used to be somebody’s kitchen. I think we’d taken down the plaster or something so you could see the wall behind it. You lose that sense of history where people remember things. Like Fly—who was an artist at No Rio, I think, in the eighties, early nineties—she comes in and she can point to things from her time in the early nineties. And other people can point to things from their time…so we’ll lose that, but what we’ll gain is a community center that I think is more open to everybody.

Comments on this entry are closed.