If you want an invitation to see James Turrell’s life’s work, Roden Crater, you first have to complete an 82-stop world tour. That’s a new requirement as of July 2013, but pretty consistent with what we know about Turrell: a moody, guarded artistic mastermind who doesn’t really care about public opinion. This is the man who’s said that the “terrible misunderstanding” between artists and viewers is that viewers often seek to have their tastes reaffirmed, while artists want to push, and hopefully, destroy, the envelope. “If you can’t submit to art, to hell with you,” Turrell has said (somewhat dramatically).

So what does it mean when Turrell becomes one of the world’s most popular artists, amongst billionaire collectors and the masses alike? I wondered this at his blockbuster retrospective at LACMA (on view through April 6th), a practical fireworks show of LEDs, holograms, dual projection cubes, and cutaway walls. Compared to the Roden Crater, where Turrell brings sky and celestial events down to earth, his museum-ready work–while typically gorgeous– have the kind of fast, high-impact wow factor which feels a little more like crowd fodder.

This isn’t so much a criticism, as an observation about a problem with no solution; art-viewing in hoards affects how art is experienced. So many people want to see the show that you have to book your $20 ticket well in advance, and LACMA times your entries in 15-minutes intervals. (Now, according to LACMA’s website, you can only see the show if you get a membership). Once in, it’s a little like moving through a crowded funhouse where you’re just trying to get to the end without clogging up traffic behind you.

This is a problem for art which aims for perceptual shifts. When Turrell becomes a main cultural activity, the work becomes less about waking ourselves up to the world’s realities—suggested by Turrell’s frequent references to Plato’s Cave—and more escapist fantasy. “We really do create the world in which we live,” Turrell observes from an Art 21 special feature. In blockbuster museum shows, that world looks increasingly far from Earth.

Still, there’s no shortage of transcendentalism; Turrell can physicalize light so much that walls melt away. I almost mistook “Key Lime”, a lime green light sliced with knifelike bands of yellow and orange, for a flat rectangle, until somebody’s cough echoed deep into the space; on second inspection, light goes from square to cube. And an almost religious aura surrounds the dimmest work “St. Elmo’s Breath”, a purple rectangle flanked by dim orange squares, which really does seem to be breathe. Less successful works like holograms and dual-projection pyramids continue to sculpt light, but in a crowded room, they don’t pull off the same gestalt.

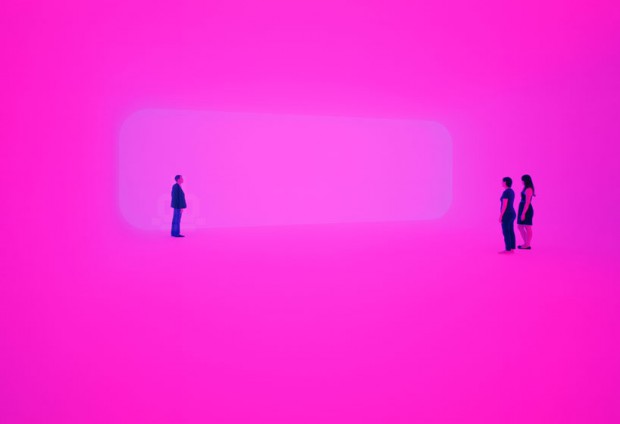

The real mindblower, though, is the grand finale: “Breathing Room,” a room on a platform with with two opposing colored light sources, and a second chamber which appears to be a flat wall of light. “You’ve now stepped into the Twilight Zone!”, joked a security guard, a la Willy Wonka. (His enthusiasm was a welcome break from the reverent, serious crowds and generally harassed-looking staff. He’s also probably a necessity at this point, after Turrell was hit with two lawsuits in the 80’s, by visitors who’d fallen into one of his works.) But he’s right, “Breathing Room” almost does feel like entering another dimension; it’s impossible not to experience a total perceptual shift after stepping into a room of pure, changing color. Depending on the colors inside, the white wall outside would turn hunter green, magenta, and orange. “My tie is not red!” the guard pointed out. Burst upon burst of shifting colors make it all worth the half hour line and the disposable booties. Big crowds need bigger art.

But the magic wears off as soon as the guards summon you out to accommodate the next batch; between being herded into the front door and briskly swept out the last, LACMA is the ultimate master architect here. So in the absence of a private invitation out to the crater, I’ll be looking for another envelope-pusher, preferably one who speaks peon.

Comments on this entry are closed.